Balkans 2016

Balkans 2016 Albania Kosovo Macedonia

Bhutan

2018

Fewer than 1 in 10 visitors to Bhutan get to see the Haa Valley. In one way, that’s a bit surprising because it is situated just a few hours’ drive from Paro (where the country’s international airport is located). However, its proximity in kilometres is not matched by its proximity in time, as the roads in and out of the Haa Valley are narrow, twisting and hardly conducive to fast or comfortable travelling. Furthermore, there very few of the “monumental sights” that seem to appeal to tourists, and it is said the main reason to visit is to experience Bhutanese life off the beaten track, and perhaps in a farm lodging overnight.

We saw it a little differently, being a more roundabout way to travel from Thimphu to Paro that provided opportunities to see typical farming activities, small villages, highland lifestyles – and a few sights that while not monumental were genuinely interesting.

Because we knew that the driving conditions for the day would demand slow driving, we set off from Thimphu fairly early this morning at about 8:00 am. The initial section of the drive south to Chuzom was fairly quick and smooth, but the road narrowed considerably as we continued south along the western side of the Wang Chuu, climbing steadily into the hills as we did so.

For a long day’s driving, Bhutan’s yellow-and-black road signs never ceased to bring amusement. I mentioned some of these in my Day 4 report, and among the notable road signs that were new today were:

• On the bend, go slow friend.

• Peep peep, don’t speed.

• Safety first, speed afterwards.

• Nature does not hurry yet everything is accomplished.

• Driving and drinking is a fatal cocktail.

• Speed thrills but kills.

• For safe driving, no liquor imbibing.

-

•Fast won’t last.

-

•Enemies of the road, liquor speed and load.

• Life is short, don’t make it shorter.

• Mountains are a pleasure only if you drive with leisure.

• One who drives like hell is bound to get there.

And the prize winner for the road sign that contains the most gender-based assumptions in the fewest number of words goes to:

• Don’t gossip, let him drive.

We stopped every so often for photos and to stretch legs, but I doubt most travellers would have been quite so interested in the things that appealed to me – farm workers labouring intensively in the fields, a sawmill adorned with prayer flags, a school housed in a former jail on the edge of a cliff from which disobedient prisoners were pushed to their deaths, terraced cultivation, and a recent landslide.

We reached Haa at about midday, and made two visits before lunch. Our first stop was the Lhakhang Karpo (or White Temple), and it was related to our second visit, which was to the Lhakhang Nagpo (or Black Temple). A local legend tells how the 7th century Tibetan King Songtsen Gampo was looking for auspicious locations to build two new temples. He released two pigeons, one black and one white. The White Temple was built where the white pigeon landed and the Black Temple was built where the black pigeon landed. This tale seems to negate every theory of geographical location I have ever taught in my classes!

The White Temple served as a very impressive introduction to Haa. It was renovated just a little while ago – indeed, the renovations are still underway –and enlarged as part of a recent visit by the King. Today, the White Temple comprises a large central dzong (fort-monastery), which is flanked by two new buildings that serve as classrooms and dormitories for about 50 monks who live on site. Helpfully, the walls of the White Temple are white.

I don’t think I have ever been welcomed by such bright, hospitable young monks as the students at the White Temple, who were keen to approach me and use their extremely limited English to converse (hello) and ask questions (how are you?, which country are you from?). I was also shown inside the temple, which had the regular array of statues one would expect, together with the area’s local deity, App Chundu.

A short five minute walk up the hill behind the White Temple brought us to the Black Temple, easily recognisable because of its sinister looking dark grey walls. Approaching the temple, a monk shouted at us to go away. Dhendup explained that the temple is seldom opened for non-residents of Haa because the deities in there are so powerful that even looking at then can kill non-believers. The Black Temple is strongly within the Tantric Buddhist tradition, which embraces an array of spirits that even most Buddhists cannot identify. Haa is a stronghold of this tradition, and indeed, in the 11th century, Haa was the place where the famous female Tibetan Tantric practitioner Machig Labdrom perfected the technique of visualising one’s own dismemberment to achieve ‘ego-annihilation’.

After a lovely buffet lunch, we spent some time wandering around the streets of Haa – or more accurately, its main commercial street. Over half the area of Haa is off-limits to local people and visitors alike because it is occupied by a vast Indian Army base, known officially as IMTRAT – the Indian Military Training Team – and an accompanying much smaller Bhutanese army training camp. The presence of the Indian military base in Haa is seen as a mutually beneficial arrangement between Bhutan and India to stop Chinese expansion into Bhutan, which has been threatened on numerous occasions. The army camp is vast, partly because it includes a full size golf course and it houses Haa’s dzong (traditional fortress). Built in 1915, Haa’s dzong today houses several Indian Army offices and a rations shop, so needless to say, it is firmly closed to visitors.

Haa’s main street was beautiful, comprising rows of traditional Bhutanese buildings with their traditional decorations, and in a few cases, even sets of prayer wheels astride the front doors so shoppers could whisk off a quick prayer when entering or leaving the shop. Unfortunately for the shop owners, business in Haa is far from brisk, and the slow pace which charms its (very few) visitors also spells financial hardship for the town’s entrepreneurs.

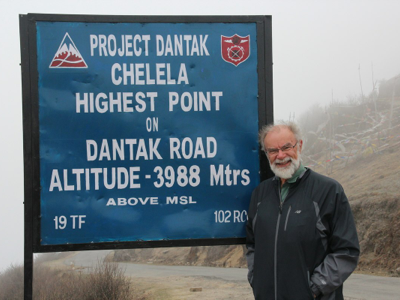

We left Haa at about 2:20pm to start the 65 kilometre drive to Paro. Despite its fairly short distance, this was another slow drive because the road had to zig-zag its way up to Bhutan’s highest paved mountain pass, Chelela Pass at an altitude of 3,822 metres. A sign at the top of the pass claimed an altitude of 3,988 metres, which seemed a bit over-ambitious.

Irrespective of its altitude, Chelela Pass was cold! Situated above the cloud base today, a strong chilly wind blew across the ridgetop, causing the thousands of prayer flags erected there to thrash about more forcefully than I think I have ever previously seen prayer flags fly. The herds of yaks in the area seemed totally comfortable, but like every other human we saw there, we stayed out of the car just long enough to get some photos before returning to the warmth of the car to thaw out again. To state the obvious, we didn’t see any snow-capped mountains in the distance from the pass today, although we did feel that the snow from those far away mountains was blowing vigorously directly into our faces.

The descent from Chelela Pass brought us into sunshine again for the first time since early morning, and after passing through elevated pine forest we soon found ourselves driving through farmlands and scattered hamlets as we approached Paro.

Our arrival in Paro completed the circuit we had undertaken through western Bhutan over the previous few days. Although we had expected to return to the Drukchen Hotel, we were delighted to be upgraded instead to the Tashi Namgay Resort, located beside the Paro Chuu and within sight of Paro Airport. Apart from the comfortable room, the dinner provided at Tashi Namgay was by far the best we have experienced in Bhutan, with great Indian food and even provision of water to drink – every other hotel has provided only instant coffee or tea.

Day 8 - Haa Valley

Thursday 5 April 2018